As a psychiatrist specializing in the treatment of mood disorders, especially “treatment-resistant depression,” I have long been struck by the inadequacy of my profession’s definition of the disorder we are treating. Or, put more precisely, definitions, since the essence of depression depends a lot on what model of the mind you favor.

Varying Definitions of “Depression”

Is depression, as psychoanalysts believed in the Freudian era of the 1950s through the 1970s, a matter of inwardly directed anger, of aggression that is too upsetting to manage or settle, so that it is ultimately turned against the self, or ego?

Or, as the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) proposed—starting with the DSM-III in 1980 and continuing up to the DSM-5 today—is depression a condition in which people have five or more of nine key symptoms: depressed mood, loss of interest/pleasure, weight loss/gain, impaired sleep, physical agitation or slowing, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness, poor concentration, and thoughts of death or suicide?

Or, perhaps, in the emerging neuroscience-based model of psychiatry—which has become dominant since around the year 2000—is depression instead a matter of dysregulated brain circuits, of impaired processing of stimuli like rewards and potential threats, of an overactive amygdala that responds excessively to negative events?

As I discuss in my recent book, The Couch, the Clinic, and the Scanner: Stories from Three Revolutionary Eras of Psychiatry, in the past half-century, psychiatry has repeatedly reinvented itself. Each time, it has radically changed its definitions of mental suffering and touted new sets of possible cures.

Every few decades, it seems, we psychiatrists change our minds about the mind!

If depression is anger turned inward, the best treatment is, obviously, psychoanalysis, lying on the couch four times a week. If depression is a collection of symptoms, the best treatments are evidence-based medications and manualized therapies. But if depression is a malady of circuits, a matter of overactive hubs and sticky nodes, then the best intervention must be retuning these circuits like a violin or guitar, tweaking widespread neural networks, stimulating healthy connections while blocking dysfunctional ones—whether with targeted brain stimulation or with brain plasticity inducers like ketamine or psilocybin.

Lived Experiences of Depression

Each of these perspectives is compelling in its own way, but, as I realized in reading a recent paper in World Psychiatry (Paolo Fusar-Poli et al.), each suffers from a major flaw: They undervalue the actual experiences of people with depression. Fusar-Poli et al.’s paper, entitled “The Lived Experience of Depression: A Bottom-up Review Co-written by Experts by Experience and Academics,” refreshingly takes a novel approach: a collaboration between professionals and people who have personal experience of depression, to explore the question, What is it like to experience depression?

Perhaps not surprisingly, the answers Fusar-Poli et al. come up with don’t match any of the conventional models of the depressed mind.

In medical school, our professors were fond of quoting the famous 19th–century doctor William Osler, who supposedly advised young doctors to “listen to the patient; he is telling you his diagnosis.” Never mind that this quote can be found nowhere in Osler’s actual works, and never mind that Osler had scant patience to actually listen to his patients’ stories; it has long been a core principle in training young doctors. Close attention to the patient, close observation, and careful examination can be key to making diagnoses.

And, yet, in our main models of depression, we psychiatrists and psychologists don’t actually listen to our patients very well. Many of the profound experiences described in “The Lived Experience of Depression” are only weakly represented in the criteria used for any of these diagnoses of depression.

Who cares, one might ask?

Well, medical treatments traditionally focus on alleviating symptoms, so whatever is missing from the “criteria” for diagnosis is unlikely to command much attention as a goal of treatment. However important an experience may be, no matter how painful, if not part of a checklist, it is likely to be ignored if it persists even after an otherwise successful intervention.

Depression Essential Reads

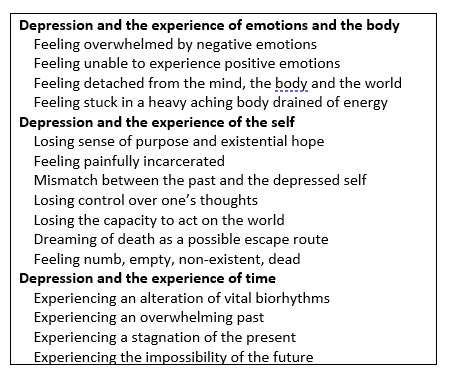

You can get a good sense of the discrepancies between clinician and patient visions by looking at the subheadings of various sections of “The Lived Experience of Depression” (I encourage people to read the whole article, but here are some that caught my eye):

The Subjective World of Depression (Paolo Fusar-Poli et al., 2023)

Lived experiences of depression

Source: David Hellerstein

To examine just one of these items: Time.

This fascinates me. I’ve never read a definition that so vividly described how depression leads to profound changes in people’s experiences of the movement of the clock:

People with depression do not perceive the normal flow of time, which appears slowed down or stopped: ‘I can’t remember days because time has stopped.’ The present drags on to what seems like an eternity in a world devoid of practically meaningful possibilities, where nothing new of significance occurs: ‘Time seemed an eternity.’

This really makes sense to me: I think of how so many patients over the years have told me that they awaken in early hours, often nightly, oppressed by an apparent stoppage of the clock, a sense of being impaled in an agonizing motionlessness in which there is no past or future, only an unbearable present.

So, here’s the question: Do our current treatments—whether inspired by psychoanalytic theory or DSM’s evidence-based brief therapies, or neuroscience-inspired transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment—do any of these treatments heal this wound, make it possible for people to feel that the clock is moving again?

I don’t actually know.

One could ask similar questions about other areas, depression’s effects on experiences of emotions and the body, or the experiences of the self, looking at “feelings of painful incarceration,” or “being stuck in an aching body devoid of energy” and other experiences of being alienated from one’s self, one’s body, and one’s society that characterize the experience of depression: How often, and how well, do our current treatments help?

I’m sure some enterprising researcher will find a way to capture these missing items and add them to lists of important “targets” of treatment. No doubt we will soon have symptom scales and checklists to measure their severity and improvement over time.

Which is great. And long overdue.

Papers like this one give us doctors and therapists more focus: We need to find out how our existing (or new) treatments can alleviate these key aspects of these impairing, often life-destroying, maladies.

The Couch, the Clinic, and the Scanner

Source: Columbia University Press

But, to me, there’s something even more important, beyond better understanding of the key features of disorder, and beyond the crafting of more effective treatments.

That is, the increasing likelihood that a collaborative process between doctors and patients can lead to a better definition of what is wrong, and potentially lead to better outcomes. To me, that is the key thing. Not just for “psychiatric disorders” (which are of course maladies of mind and brain and body) but for “medical” ones as well…in cardiology, gastroenterology, obstetrics/gynecology, cancer care, etc., etc., throughout all specialties of medicine.

Thus, the greatest contribution of “The Lived Experience of Depression” may be its effort to bridge the vast distances between health and disease, between suffering and recovery…and to begin to redefine the goals of treatment across all specialties of medicine.

That could really lead to better outcomes.

+ There are no comments

Add yours