MASH (Mobile Army Surgical Hospital) unit from the Korean War, 1952

Source: Unknown / Wikipedia

This is Post 2 of 2 introducing the “Push Paradigm.” Read Post 1 here.

“We are at war. And we are going to lose some students,” a school therapist recently told me. It was a distressed, if not matter-of-fact, assessment of campus realities for both students and counselors.

The “we” she is referring to are campus counselors. The ”war” is the extreme student mental health acuities they treat, namely suicidality. One of the consequences of triaging in wars is that the most serious “injuries” get the most resources. Lesser injuries have to wait. There simply aren’t enough resources to treat everyone right away, including those who may be too resource-intensive (yes, most schools have policies that allow them to administratively or involuntarily withdraw students who consume too many school resources, including mental health resources). It’s a gobsmacking and visceral image to drop a MASH-style triaging unit into the heart of campus mental health.

Student Mental Health Front Lines

A mental health “war” is definitively not the picture that is painted on most four-year college CAPS (Counseling and Psychological Services) websites.

The expectations set for students by campus services are that care is readily and ubiquitously available with 24-hour crisis lines, peer counseling groups, roaming “CARE” teams, digital mindfulness assets, and counseling centers with therapists waiting to help.

Juxtapose this with the experiences of many four-year university students: They can’t get an appointment. Appointments are at difficult times. Wait times may be too long. Maybe the center is located in a place they don’t want to be noticed (due to stigma, shame, embarrassment, etc.). Or maybe their mental health challenge isn’t acute enough to warrant being seen.

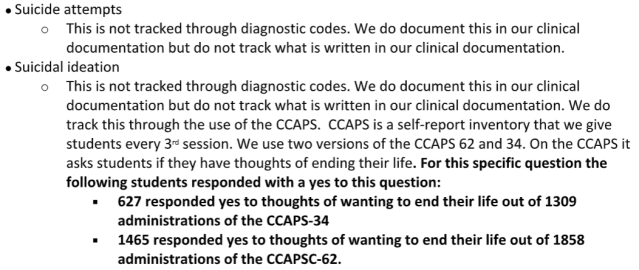

Many four-year campuses are compelled to triage for the most acute pathologies (i.e. suicidality), leaving less acute students unserved or underserved. I’ve heard this time and again in interviews with campus counselors and therapists. But I wanted to balance this qualitative data with specific quantitative data. So I conducted public records requests of numerous colleges. One of the campuses that responded was California State University, Fullerton. The request I made to CSUF and about 15 others was as follows:

Hello,

I am requesting records about anonymized Cal State Fullerton mental health trends that the counseling center should have available. I have four specific asks, enumerated below.

ASK #1:

Specifically, please provide the weekly or monthly average number of counselor-supported incidents or visits or counselor interactions that covered the following topics:

Suicide attempts, Suicidal ideation …. [and there were several others, but for brevity sake, I’m truncating].

I’ve screenshotted the relevant portion of the school’s Public Records Request response:

Screenshot of a portion of a report obtained via FOIA request sent to the author.

Chris Drew

Between 48 and 79 percent of students who had been to this center at least three times reported wanting to end their life. Numbers like this are by no means universal. We all know that the mental health crisis is bad. But they vividly illustrate the cruxes of this article, which are:

- There are a ton of people who simply cannot and do not access mental health support systems due to innumerable frictions

- There’s no room in the current system for being able to apply “an ounce of prevention.”

This latter point is almost never seriously considered.

Do Not Blame Counselors

It is essential to state explicitly that this is not a castigation of campus counselors, counseling and psychological services, or mental health care workers in general. Campus counselors are over-taxed. Many student-counselor ratios are greater than 1,200-to-1.

This is a reflection of the evolved mental health battlefield and consumer expectations. If our algorithmically dominated, lived experiences include Amazon knowing what widgets we desire, Netflix predicting what entertainment we crave, and Facebook foretelling the next travel experience we yearn for, it’s natural we should expect someone to be prescient about how we might be feeling, including college counseling centers.

Part 1 of this series highlighted why so many have an implicit expectation that our friends, family, coworkers, and even therapists should possess an innate understanding of the factors driving student isolation, stoking student stress, igniting student anxiety, plunging students into the abyss of depression, or worse. So why don’t we have such insights?

Old Pull Paradigm vs. New Push Paradigm

The Pull Paradigm still works for a lot of people. Millions of people. But the Pull Paradigm continues to lay the expectations at our feet for us to:

- Self-identify struggles.

- Sift through the complexities of available resources.

- Surmount the daunting frictions of scheduling, cost, stigma, and shame.

We need to ask: Are the steps in the process of the old Pull Paradigm still serving the well-being of the majority of our students’ — or our first responders, health care workers, veterans, and others, for that matter?

The Push Paradigm of mental health support eliminates all the frictions of the pull approach.

Pushed support comes to you, based on your subtle digital and real-life signals. We call these signals subtle “hand raises.” And the support comes in the form of small acts delivered by your tribespeople—your friends, family, teammates, coworkers, or even your therapist or counselor. Actions pushed to you by people you know.

We call this “activating your tribe.” I developed the Push Paradigm with my organization, VEXT. And it looks like this:

Reading Subtle Signals. Every day, we emit a symphony of subtle—often undetected—signals. They manifest in a catalog of commonplace ways: our expressions, movements, dietary choices, social interactions, and even our digital exhaust. As well, we have robust digital lives measured in all sorts of ways. These biomarkers include number of steps, amount of sleep, and even heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and more. Collectively these are the digital and physical breadcrumbs of our modern lives. And they can be key to not just understanding but also predicting aspects of our mental well-being.

Activating Our Tribes. A therapist recently said to me, “You don’t have to be a therapist to be therapeutic.” We just have to be there. We can use these breadcrumbs to help us “be there” for our tribespeople. Many of us need to be nudged to recognize these signals. We’ve become somewhat rusty at both broadcasting our signals and decoding those of others. We need help being a better tribe to our tribespeople. Just as our smart watch might nudge us to stretch our legs, digital nudges can activate us to connect as a friend.

Customizing Connection. Small, positive connections sprinkled throughout our tribal interactions can serve as preventive measures for individual mental health. Knowing that we have too few steps or have not interacted socially in a while can lead to timely prompts for us to go for a walk, have a phone chat with a friend, give a high five, get a hug. And it’s not just about preventing suicide. It’s about decreasing isolation. It’s about removing digital intermediaries and being face-to-face humans.

Our Siloed Mental Health Experiences

Think about the average mental health journey as a siloed experience. Most of us keep it largely to ourselves. If we use some type of mindfulness app, that data remains privately tucked away in the bowels of the servers of said app (where it may or may not be used for advertising purposes). If we see a therapist, again, that is between us and said therapist. The people around us never know how we truly feel. How isolating.

What if some of our mental health data—with our permission, of course—could be anonymously shared with friends or community members we know?

What if our tribespeople could see a pattern that on Tuesdays and Wednesdays one of their tribespeople reports feeling down? And what if they could also see that on those days that person doesn’t seem to be very physically active or has a low number of social interactions? Maybe they could recognize a pattern that at the end of each quarter another member appears to sleep only 5 hours a night and has elevated heart rate patterns throughout the course of a day?

Better yet, what if the devices in our back pockets could recognize these patterns and vibrate with suggestions of things to do with or for those people and provided a means to connect to boot?

Activating our tribe in these ways helps decrease stigma, increase awareness, and spur people to take action at just the right time with those around them.

These principles are core to the methodology I’ve designed and the technology I’ve built. Most people want those around them to know how they’re feeling. We just don’t want people to know it’s me who’s feeling that way.

It’s that second statement that remains a barrier to a tribal approach to mental health in the U.S. But it can be overcome. And we overcome in part by sharing our data with our groups in a protected-enough, anonymized way so that our tribe can know. And we can trust that data won’t be used to threaten matriculation, playing time, graduation, a job, a promotion, etc.

Pushed Mental Health Mindset

As we contemplate the evolving landscape towards a Pushed Paradigm of mental health, the central question isn’t merely, “How can campuses and institutions provide more mental health resources?” Instead, it’s something like, “How can we attune ourselves to the signals within our tribe, recognizing who may need us and when?”

The cool thing about this question for campus and institutional leaders—and this isn’t applicable only to students but to first responders, healthcare workers, active military and veterans, and more—is that we don’t even have to answer it 100 percent correctly.

If we start adopting the mindset of this question—and building for the expectations that belie it—we may start building something that looks like mental health herd immunity across our campuses.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7 dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

+ There are no comments

Add yours