Co-authored with J. Jeffrey Gish, Assistant Professor of Management, University of Central Florida

A compelling research literature indicates that leader behaviors can shape the prevalence of sexual harassment in a given organization. A similarly compelling research literature indicates that the prevalence of men at higher levels in an organization’s hierarchy can also shape the prevalence of sexual harassment in a given organization. Too many men at the top, and leaders who tolerate sexual harassment, tend to result in more sexual harassment.

We appreciate the importance of these findings, but examined a question that moves a step beyond these findings: Can a CEO’s facial masculinity affect the degree of sexual harassment in an organization? In other words, above and beyond the CEO’s gender, behaviors, and even statements about sexual harassment, can their basic appearance also have an effect? This is especially relevant to new employees who have relatively little information to go on about their CEOs, but who often see images of their CEOs throughout their physical and online workspace.

To conduct this study, we first started by developing the concept and measure for what we call “presumed patriarchy.” This draws from a long and ongoing conversation about patriarchy in our contemporary society.

Our angle on this topic of patriarchy is that employees may look at the information available to them and use it to judge the degree to which they believe patriarchy is present in their organization. Specifically, we define presumed patriarchy as “an explicit or implicit assumption about prevailing organizational values favoring men as more deserving of power, influence, responsibility, and rewards than women”.

We posit that a CEO’s face can convey information that employees use in their judgments regarding presumed patriarchy. People make interpersonal judgments based on appearances all the time. We simply apply this idea to how employees judge their CEOs and what this means for what their organization values.

To see the full academic version of our paper forthcoming in the Journal of Management, visit this link: https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063231206351

For the full version of the academic article documenting this research, see our forthcoming article at Journal of Management: https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063231206351

When the organization places someone with a highly masculine face in the top role in the organization, it may implicitly send the message to employees that masculinity is valued. Obviously, there are other factors that shape the judgments of employees about what is valued, such as the words and actions of that CEO as well as the prevalence of men within the leadership ranks of the organization. But we posit that the CEO’s appearance will be an additional factor that employees pay attention to and use in generating their expectations. Accordingly, we propose that CEO facial masculinity will be one factor that positively influences employee perceptions of presumed patriarchy in the organization.

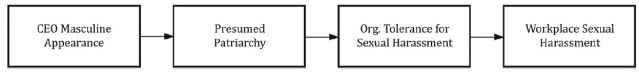

The rest of our conceptual model is pretty straightforward. In organizations in which employees presume the existence of patriarchy (which is likely less than perfectly correlated with patriarchy from a more objective standpoint), employees will perceive that there is more tolerance for sexual harassment. That perceived tolerance for sexual harassment will lead to more enacted sexual harassment. Thus, overall, we propose that CEO facial masculinity will have a positive effect on employee sexual harassment, through the intermediate mechanisms of increased presumed patriarchy and increased perceived tolerance for sexual harassment.

J. Jeffrey Gish

We tested our hypotheses over the course of three studies. The first study used 10 years of anonymous online employer review data from Fortune 500 companies to show that more masculine-appearing CEOs lead organizations with more sexual harassment.

We recruited an independent sample to rate the masculine appearance of Fortune 500 CEO photos. We then compared those ratings to online reports of sexual harassment and detected a significant relationship between more masculine-appearing CEOs and greater instances of sexual harassment, controlling for the overall number of employee reviews, industry, revenues, total number of employees, return on assets, and total shareholder returns.

The second study developed a scale for presumed patriarchy and used experiments to examine causality. We created prospective employer information for a fictitious employer, including a photo of the company’s CEO, and randomly assigned participants to one of two conditions. One condition contained a photo of a very non-masculine appearing CEO and the other a photo of a very masculine appearing CEO (third-party ratings established the degree to which a given CEO had a masculine appearance). The results of this experiment suggest a positive causal link between CEO masculinity and presumed tolerance for sexual harassment at the focal organization, mediated by presumed patriarchy.

The final study examined employees who had been hired for a new job with a male CEO but had not yet reported for the first day of their job. We asked these organizational newcomers to find a photo or video of their new CEO online and rate how masculine he appears. These masculinity ratings predicted the new employee’s evaluations of presumed patriarchy at their new job.

After the employees were onboarded, in their first month on the job, we surveyed them again to determine the organization’s tolerance for sexual harassment and the number of times the employee had experienced or witnessed sexual harassment. The results indicate that more masculine-appearing CEOs have employees who presume greater patriarchy, and those presumptions are met with greater perceptions and experiences of sexual harassment at work.

Overall, we find pretty clear support for our hypotheses that CEO facial masculinity will increase presumed patriarchy, perceptions of tolerance for sexual harassment, and ultimately sexual harassment. These effects seem to occur above and beyond the more typically studied predictors of sexual harassment, such as the degree to which women are represented in the upper levels of leadership of the organization, as well as the words and deeds of the leaders.

It is worth noting again that our clearest evidence is for new employees for whom information about leaders and the organization is scarce. It is quite reasonable to expect that the effect of CEO masculinity on a new employee’s perceptions and behaviors may weaken over time as the employees gain more experiential information about the actual policies, norms, and behaviors in their organizations.

As that occurs, those experiences and observations may become much more powerful in shaping their beliefs and behaviors regarding presumed patriarchy and tolerance for sexual harassment. That said, it is still quite interesting that even just at organizational entry there could be a detectable effect of CEO facial masculinity on sexual harassment.

It is unreasonable to expect that CEOs will readily change the degree to which their faces have a masculine appearance. This is not the implication we are trying to draw from our research.

For us, it makes more sense to focus on how some CEOs (and perhaps other leaders as well) may need to go to extra effort to communicate the degree to which women are valued in the organization, and that sexual harassment is not tolerated. We believe that CEOs can counteract the effects of their appearances on employee behaviors, but it likely requires deliberate actions on their part.

+ There are no comments

Add yours