I was doing a podcast the other day, and the interviewer inquired, “You use ‘justification’ a lot and often in ways I have not heard it used. Can you help our listeners by explaining what you mean by the term?” I was grateful for the question because I do use the word in a somewhat unusual way. This is because I have studied the word carefully, and I have come to believe it is the single-most-important word in human language. I acknowledge that this is a pretty strong assertion! Hopefully, by the end of this post you will see why I feel justified in making such a strong claim.

Let’s start with the basics. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary gives the primary definitions of justification as (a) the act or an instance of justifying something and (b) an acceptable reason for doing something. It also defines justifying as acting to prove or show to be just, right, or reasonable. So, justifications are the reasons we give for doing things. They are also the reasons we have for believing things, and justifying is the process by which we try to get other people to see our reasons for our claims and actions.

For many people, when they think of the word, it evokes people trying to defend themselves from accusations. An example might be of a teenager who tells his parents that he was drinking because “all his friends were drinking” and they pressured him to do it. We can call this the “rationalizing” meaning of the word justification. We can associate this meaning with Sigmund Freud because one of his central insights was that we often generate self-conscious rationalizations to protect ourselves socially, but that they hide deeper, largely unconscious motives.

Epistemology

But the Freudian meaning of justify as rationalize really is only one meaning of the term. There is another meaning that is almost the polar opposite. To understand it, we can shift from Freud to Plato. Plato was a Greek philosopher who had an enormous influence on Western thought. One of his more influential ideas was the way he formulated epistemology. Epistemology is a term in philosophy that refers to how we know and what we deem to be true knowledge.

Plato developed the “JTB” formulation of epistemology, which refers to “justified true belief.” This is the idea that we have knowledge when our beliefs about the current state of affairs are (a) accurate and (b) we are justified, meaning we have good reasons for our beliefs. To see this clearly, imagine there is a chemist who has a 5-year-old son. Let’s imagine the chemist happened to say to her son that water is made up of H2O. If we ask the son, “What is water?” and he says H2O, he is saying the right answer, but he is not justified in his knowledge. However, his mom is justified in her knowledge. So here justification refers to the network of claims that legitimize knowing as true knowledge.

Let’s take a step back and think about these two meanings. One, the Freudian meaning, refers to how we generate justifications to hide our true motives and navigate the social world. The second, the Platonic meaning, refers to the analytic process of developing good reasons that describe and explain the world accurately. These are basically opposite. Consider, for example, that we can think about science as the process and methods by which we generate good justifications for how the world objectively is, factoring in our subjective position and moral evaluations.

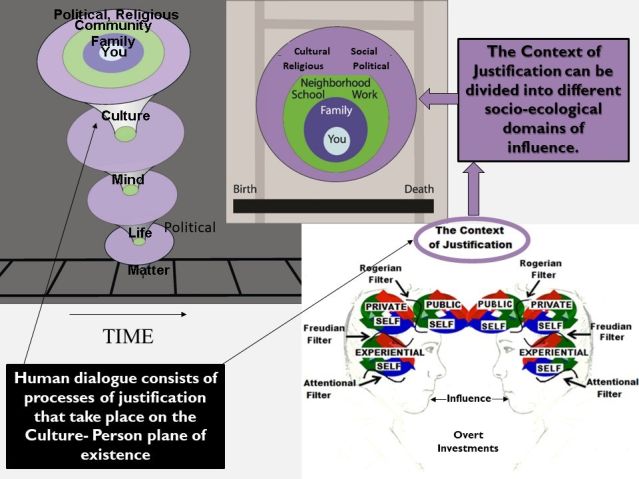

UTOK, the Unified Theory of Knowledge, has its start in 1996 because of a key insight I have about justification. Specifically, I see that processes of justification emerge when human language gets organized into propositions. The reason is that propositions set the stage for questions about the extent to which they are justifiable. This generates a “question-answer dynamic” that builds systems of justification.

Ontology

This claim about how humans interact via language brings us to another important word in philosophy, which is ontology. Ontology refers to what is real or one’s theory of reality. As Plato’s analysis makes clear, most in philosophy think about justification in terms of epistemology. In addition, when everyday folk hear people give justifications, we try to decipher whether the person is really justified or if they are just rationalizing.

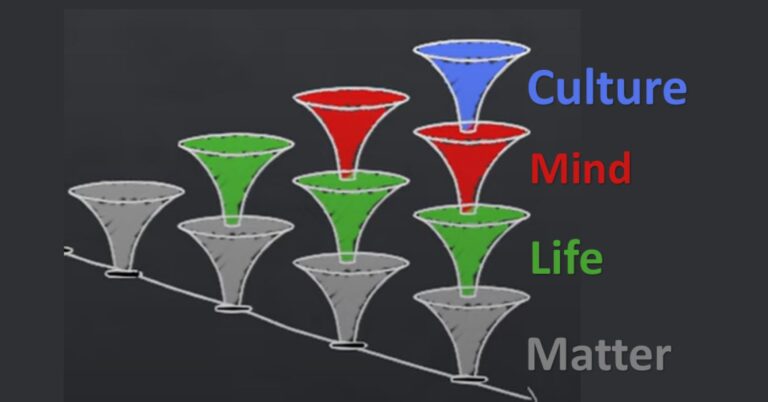

UTOK gives us a new perspective on justification. In addition to noting the epistemological aspects of justification, UTOK allows us to see clearly the ontology of justification systems. That is, UTOK’s “Justification Systems Theory”1 (Henriques, 2022) frames justification processes and systems as real things in the world. In fact, justification processes and systems are the glue that binds together what UTOK identifies as the “Culture-Person” plane of existence. That is, our propositional knowledge is bound together, structurally and functionally, by systems and processes of justification. And, as children, we are socialized to become fully functioning adult persons by learning what is and what is not justifiable in our culture, community, and family.

Source: Gregg Henriques

I will conclude my justification for why justification is the most important word to know about human language with a summary of the concept from my 2004 article, “Psychology Defined”:

Unlike all other animals, humans everywhere ask for and give explanations for their actions. Arguments, debates, moral dictates, rationalizations, and excuses all involve the process of explaining why one’s claims, thoughts, or actions are warranted. These phenomena are both uniquely human and ubiquitous in human affairs. In virtually every form of social exchange, from warfare to politics to family struggles to science, humans are constantly justifying their behavioral investments to themselves and others.

+ There are no comments

Add yours